FLEXIBLE PERIODISATION: THE KEY TO BALANCING PERFORMANCE, INJURY PREVENTION AND RECOVERY

- Admin

- Jan 8

- 5 min read

Periodisation is a big part of a successful strength and conditioning program. In essence, it involves forward planning to ensure training volume (the total amount of work completed) and training intensity (the effort applied to that work) are in line with your end goal and injury prevention. While typical periodisation in sporting S&C involves breaking a competition period down into cycles and individual training days, each with their own focus following a pre-determined model of periodisation, first responders often require a slightly different approach.

"First responder S&C is about maintaining 80-90% readiness year-round."

For starters, first responders are not blessed with an off-season, there is no peaking for competition or deployment, deloading during gameday -2 and gameday -1, and no recovery sessions on a Monday morning. Every day is a potential grand final where you may be required to perform at your best, so rather than building to peak readiness around a specific time of the year, first responder S&C is about maintaining 80-90% readiness year-round.

Linear and Block Periodisation

That means a traditional linear periodisation model is not necessarily the most appropriate. For a competitive athlete, linear periodisation involves starting with higher volume and lower intensity in the preparation phase, slightly decreasing volume and increasing intensity in the general phase, then lowering the volume but significantly increasing the intensity in the peaking phase, followed by a decrease in both for the recovery phase. This typically allows athletes to develop their fitness components in the off-season, maintain during the competition, and then recover afterwards.

Block periodisation follows a similar model where each training block will feature a volume and intensity appropriate to focus primarily on one specific component of fitness. The trouble with block periodisation for a first responder, is that developing one fitness component might cause another one to suffer. For example, if your training block is focused primarily on increasing your muscle endurance, your maximal strength can be expected to decrease slightly as these two fitness components do not respond to the same stimulus. This is not such a big deal during an off-season or pre-season, but in the emergency services, that affects your overall readiness on any given day.

"If you’re balancing occupational performance, recovery, and training on a block or linear progression model while managing soreness, then don’t fix something that isn’t broken."

This is not to say that these two models will not work. Individuals new to training will achieve significant adaptations regardless of their periodisation or training structure due to neuromuscular adaptations, or ‘beginner gains’, and if you’re balancing occupational performance, recovery, and training on a block or linear progression model while managing soreness, then don’t fix something that isn’t broken. However, you might be making things harder than they need to be, because there are a few periodisation models that compliment a career in the emergency services far more than the two we’ve discussed so far.

Daily Undulating Periodisation

The secret to first responder periodisation is flexibility with an aim to train concurrent fitness components. Block or linear periodisation often conflicts with occupational workload or tactical training volume which can cause injuries, fatigue buildup or a performance drop, so you need a periodisation model that allows you to increase and decrease volume and intensity accordingly in short time frames.

Daily Undulating Periodisation (DUP) does this by changing the volume and intensity from one session to the next so that each session within a single program cycle focuses on a different fitness component. Researchers working with specialist police groups found DUP was effective at improving strength, power, speed, aerobic fitness and anaerobic fitness concurrently. Using the fitness components mentioned above, you might do three sessions in the gym per week, one focusing on Muscle Endurance, one on Rate of Force Development (RFD) and another on Maximal Strength.

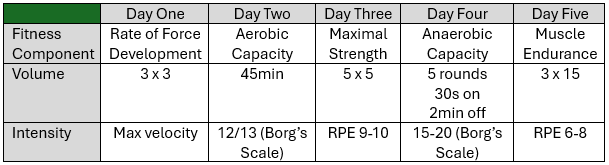

A cycle of strength training following a DUP model might look something like this:

Then, when we add cardio to the mix, we get something like this:

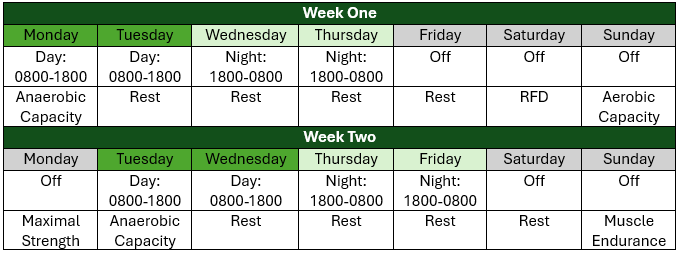

To get an idea of how this might look in reality, consider the following example using one fortnight of the typical Australian Firefighter 10/14 roster with the inclusion of rest days to balance the training load.

This is an example of a DUP program with low time commitment where training only occurs on the most recovered working day per week (first of the cycle), allowing maximum output on the other six working days. The first day after nights is also dedicated to recovery but if that’s not necessary, this could always be the zone 2 aerobic capacity day. Although the fitness components might change, this same principle can be applied to most shift work schedules.

Flexible Periodisation

"The most straightforward method of managing your volume and intensity to achieve your goals and minimise injury, is flexible periodisation."

Going back to the original definition at the start of this article, periodisation is about balancing volume and intensity to achieve training goals while avoiding injury. Ultimately, the way you approach the structure of your training will have to be unique to your needs as they relate to your occupational load, recovery, family, lifestyle and anything unexpected that might pop up along the way.

While DUP is great, it can still be a bit complex for some people. The most straightforward method of managing your volume and intensity to achieve your goals and minimise injury, is flexible periodisation.

In a flexible training program, each day is either assigned a high-fatigue, moderate-fatigue or low-fatigue rating based on the shift, hours of sleep and any lifestyle factors that need to be considered. High-fatigue days are night shift, afternoon shift, days with sleep interruption, and stressful periods of the year. Moderate fatigue days are day shift, days with poor sleep, and moderately stressful periods of the year. Low-fatigue days are days off, days with good sleep, and low stress periods of the year.

Heavy lifting, high intensity cardio and long-duration steady-state cardio are reserved for low-fatigue days. Moderate duration steady-state cardio and low RPE lifting is reserved for moderate-fatigue days, and rest days, stretching, mobility or low intensity cardio are reserved for high-fatigue days.

In the fortnight outlined above, we’ve targeted five components of fitness (aerobic capacity, muscle endurance, maximal strength, anaerobic capacity and flexibility) across eight sessions in 14 days. We’ve even allowed for a social catch-up during Saturday’s bush walk in week two, all while accommodating for the rigours of the shift work roster.

Another benefit of a flexible program is that you can make alterations on the day by simply swapping two workouts or making some simple substitutions to accommodate for soreness or unexpected fatigue. For example, if the legs aren’t recovered after the bush walk on Saturday, the Heavy Lower day could be swapped for a Heavy Upper, or Low RPE Full-Body Lift.

Summary

For first responders, maintaining consistent readiness is more important than peaking for a single event. Traditional linear and block periodisation models often clash with unpredictable workloads and fatigue patterns, making flexible approaches essential. Daily Undulating Periodisation and flexible periodisation strategies allow for concurrent development of multiple fitness components while adapting to shift schedules, recovery needs, and lifestyle factors. By prioritizing adaptability and balancing intensity with fatigue, these models help ensure sustainable performance and injury prevention year-round.

Comments